Vapor pressure is a measure of the tendency of something to evaporate.

Understanding how it is measured may help to make sense of this idea.

Image a container that is truly empty (vacuum, not filled with air). The pressure inside such a box would be zero.

Now imagine that we could magically insert a small amount of a liquid into the space.

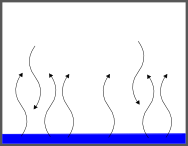

Within the liquid we know that there will me some molecules moving faster and some more slowly (Boltzmann). The fastest ones will break free from their neighbors and evaporate. As a result, there will now be pressure as these particles bounce against the walls of the container.

It might be tempting to think that the pressure in the box will continue to rise as more and more of the liquid evaporates. You may even expect that all of the liquid will evaporate, but Boltzmann comes back to haunt us here. As soon as there are particles in the gas phase, we can look at the distribution of speeds for those molecules. Some of them will be fast, but some of them will be very slow. These slow molecules, if they bump into each other, or the surface of the liquid will condense. So, while the liquid is evaporating, the gas is condensing.

Initially the rate of condensation is very slow (there isn't much gas there) but as more and more of the liquid evaporates, the rate of condensation will increase until it is EQUAL to the rate of evaporation. At that point the amount of particles in the gas phase will stop changing, and so will the pressure.

That pressure (when the rate of evaporation and condensation are equal) is called the vapor pressure.

One thing that you should know is that vapor pressure is dependent on temperature. At higher temperatures, more molecules are moving quickly and therefore more will evaporate. In the hotter gas, fewer of the molecules will be going slowly enough to condense, so more will need to evaporate before the two rates can be the same. With more material in the gas phase, the pressure of that vapor will be higher. Of course the opposite is true when the temperature is decreased. This temperature dependence means that you can look up the vapor pressure of water (and some other liquids) on a table that will tell you the expected vapor pressure at various temperatures.

The last point you should understand is that since (as Dalton's Law of Partial Pressures tells us) gases ignore each other, the box (in the example above) does NOT have to be empty to work. The change in the pressure that results from the evaporating liquid will be the same whether the pressure starts at zero (a vacuum) or at some other value

Welcome to aBetterChemText

Why aBetterChemText?

What is aBetterChemtext? aBetterChemText is intended to be a new way to look at Chemistry. It is written in plain English to make it acc...

Monday, July 8, 2019

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

-

The Beginnings of Science and Chemistry This thread of history takes us through Ancient Greece , through Northern Africa during what is cal...

-

There are many real-world applications of the laws discussed in this section. They include: How you use a straw sucking in your cheek...

-

In the discussion of Planck’s work, I suggested that we could understand quantization as being like money - everything is a multiple of the ...

No comments:

Post a Comment